The foundations of thinking are fluid and non-logical

A more granular syntax of cognition

By Yervant Kulbashian. You can support me on Patreon here.

Is the human brain inherently logical?

This simplistic question has an equally simplistic answer: the brain is sometimes logical and sometimes not. When calculating mathematical equations or writing software, it may proceed logically. When fantasising, or creating art, or forming political opinions, considerations of logical consistency may get ignored as unimportant.

Although popular, this easy answer really dodges the question. Any kind of logical thinking is by its very nature rules-bound and universal, meaning it does not admit of exceptions or subjective whims. It is defined by its rules and how they are applied. If you can at any time break these rules, or ignore them due to laziness, ignorance, or preference, then they cannot be automatic or built-in functions of the brain. If it is possible for me to believe that all my neighbours are good people, and that Mary is my neighbour, and yet I can also believe that Mary is not good — in other words, if I can be logically inconsistent — then my application of that logical rule is always optional.

And “rules” in this context can be any structured method of forming new beliefs, for example:

- Deductive: e.g. If all swans are white, and Greg is a swan, then Greg is white.

- Hierarchical: e.g. Mumbai is in India, India is in Asia, so Mumbai is in Asia.

- Causal: e.g. Pushing the ball will cause it to roll. I pushed the ball, so it will roll.

Or any other rules-based thinking you care to invent. The point is that whenever I apply any of these I must have chosen to constrain my thinking to it, and even had to learn the proper way to apply it in my situation. And any machinery of thinking that is allowed to pick the appropriate application of a logical rule cannot itself be constrained it.

Introspection reveals that one’s stream of consciousness is naturally disjointed and accidental, with no innate necessity that you build up a coherent structure of beliefs about the world, not even in the long run. Society will no doubt encourage you to be self-consistent, and teach you how through rigorous education in critical thinking. Yet the fact that logical rules are so difficult to teach, and even more difficult to regularly and correctly adhere to should cast serious doubts on our image of the brain as a naturally logical machine — even in part.

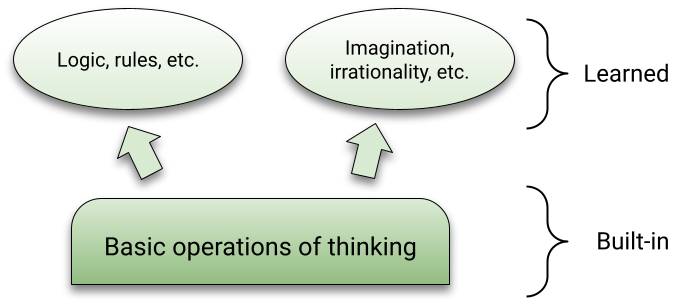

Of course, the infrastructure of the mind must still be able to construct and carry out logical operations — e.g. quantifiers like “all” or “none”, connectives like “xor” or “and”, hierarchies like “inside” or “part of” — or at least to roughly approximate them somehow. But this is only a functional prerequisite. It is not what causes you to constrain your thinking to a logical rule in a given situation, nor does it explain how you are able to do so.

As an analogy, the physical body of a baseball player must be able to play the sport, but that does not necessarily mean he ever will unless he chooses to — and usually with great effort. It would be odd to say that his body was hard-coded to follow the rules of baseball, or that there is a built-in “baseball” subroutine he can call on. Those abilities must be composed out of more basic operations: lift your arm, curl your fist, etc.

As with the baseball player, there must be some deeper, freer, more generalised set of operations on top of which logical thinking is constructed, and by which its various applications are guided. If our goal is to describe the behaviours inherent in all thinking we must define a set of operations that all thoughts follow, without exception.

At first sight, all we can confidently say about human thinking is it involves the ability to conjure up some mental image or sound; for example, when the thought of a bird makes you think of a wing, or of flight. Putting aside for the moment how you learned this association¹, the set of mental events in themselves does not contain any logical structure or argument. It is non-logical, just one image leading to another. They are like frames of a movie automatically following on each other, with no claim about their content or internal relationships.

To make it “logical” it must first somehow become some kind of assertion: e.g. “all birds have wings”, or “some birds fly”, or “the bird is on top of the box”, or “there is one bird, not two”. Whether done in linguistic terms or otherwise, making it an assertion adds something new to the thought². The original images could have continued to act on your mind without this addition, as a stream of consciousness or haphazard association, like a fluid daydream that never repeats.

The mere act of identifying the subject of a thought using a category-term like “bird” is itself an extension on the original. When you thought of the bird or the wing, it was only a ambivalent image, a particular memory. There was nothing general about it, nor any identification of its contents. The image may incidentally have contained a background sky or building that was not inherently part of the bird. To convert it to the symbol “bird” is to subsequently imagine that the thought generalises into something that you and other people can repeatedly latch onto; as a real thing, perhaps representing a whole group of persistent things (birds).

None of that was part of the initial thought-image. That image just occurred and nothing else. It may never occur again, or if it does, its identification and properties may be mercurial — it could be interpreted as a pigeon one day, and a morning dove another. This flexibility is part of its strength, since it lets the image cross borders between various useful systems of interpretation. Generalising it as the symbol “bird” actually places limits on thinking, since it asserts that the many instances must be the same thing (bird), instead of many separate things (images). So even the most basic logical principle that A is equal to A — that a thing must be equal to itself — is actually a choice and need not be observed at all times, since a person may have wildly varying thoughts on a matter as guided by their momentary whims.

Of course, thinking is not entirely random or disconnected. The mind naturally responds similarly to similar experiences. If it didn’t, thinking in general would not be possible, since the world would be brand new in every moment, and past learning would not be able to influence the present. So it may be that when you next see a similar-looking bird in front of you, the memory of it flying pops into your mind. You may now react as though this were something real, say, by trying to cut off its potential avenues of flight. Implicitly you appear to have made an assumption — “this bird will fly, just as the one in my memory did”. You could even formulate that as the logical premise “all such birds can fly”.

But it does not follow that the mind believes this premise simply because it reacted to its imagined visualisation. The connection between what you saw and your existing memory was loose and accidental, based on rough and inconsistent pattern-matching; and there was no claim about generality between the two instances. The recollection merely functioned like a momentary passing hallucination, without any guarantee of future consistency. All raw thoughts are such entities — simple mental images and sounds that make an appearance, and to which you react; yet whose generalised truth-value is not yet ascertained.

Minds can function perfectly well — and do, in fact — without any of the added modifications that are required for logical thinking. Any “language of thought” like logic must be electively learned and consciously maintained. So why would your brain would go the extra mile and frame its thoughts according to logical constraints in some situations, and not in others? What triggers this shift in mindset, and sets it to such an activity?

We mentioned above that logic of any kind can only be applied to assertions. Assertions are symbolised statements about consistent and generalised entities, e.g. “all birds fly” or “there were two apples, and I added two more”. Linguistic terms like “bird” or “apple” help this process along, because, as mentioned, symbols are recurring patterns of sights and sounds that can unify a set of disconnected instances. They take advantage of the automatic pattern-matching system already in place — thinking of “APPLE” (the word or sound) will have similar effects across time. This lets you lock down the fluidity of the mind (and also of the world) into logical units.

Working with symbols is not an automatic process, however. As discussed in another post, you learn symbols primarily to meet the requirements of interpersonal communication, as a sort of enforced civility and alignment of mutual intentions. Abiding by the strictures of logical systems is a socially useful choice a person sometimes makes to coordinate their thinking in harmonious concord with their peers. This is why logic is so tightly tied to language. (The term logic even comes from the Greek logos, meaning “word” — logic belongs to language.)

Natural thinking on the other hand is so much broader, and the machinery that drives it so much more versatile, that to reduce all thinking to logical operations is to describe only one concretized possibility in a much broader landscape. If our goal is to describe the entirety of human intelligence, including all its capabilities and possible skills, now and in the future, we must step out of the straight-jacket of logical reasoning and allow the mind to attach any manner of thoughts, whether true, false, real, unreal, reasonable, fallacious, or some mixture, without enforcing that it always make sense.

One can find many theories in practical AI research that go beyond direct stimulus-response and build internal representations on which they then operate. It is perhaps lamentable, then, that they all rely so heavily on structuring thinking in logical terms. This is almost by necessity, since to structure thinking ultimately requires choosing a set of constraints, then enforcing consistency across them through automated routines. Models like Belief Networks and Logical Tensor Networks, and more generally, neurosymbolic AI, which is defined as

The integration of neural models with logic-based symbolism

all attempt to automatically extract symbols from unstructured data, then reason across those according to fixed logical operations:

Symbolism has been expected to provide additional knowledge in the form of constraints for learning — Neurosymbolic AI: 3rd wave

This impulse is understandable. It is easy to look at human thinking and draw the conclusion that brains have a natural “language of thought” — a framework of rules or set of operations that is built right into the hardware. From this it is tempting to want to impose the same structure onto AI architectures; especially when you can see no other way to get the AI to regiment its thinking.

This approach is certainly useful when we intend an AI agent to accomplish some narrow productive task co-defined by its creators: e.g. put the right number of items on a shelf, drive safely through a busy intersection. However, it constrains the agent to those interpretations that were predefined as useful to accomplishing the specific task. When embedded as part of the indelible infrastructure of the AI, the agent can no longer choose how it applies those rules on a case by case basis.

Ultimately this approach ends up being overly restrictive, and lacks the flexibility and adaptability that makes human thought so versatile. The agent inevitably comes up against exceptional cases which are deemed irrational by the aforementioned standards. For example, an autonomous car may for some reason have to drive through an unpaved park, or on a beach, or even on a sidewalk; at which point all assumed categories and the logical deductions derived from them break down.

This contributes to the well-known long tail of failures that continues to bedevil Machine Learning engineers and hinder wider adoption of the technology. It should come as no surprise that all practical implementations of automated logic in AI have produced lacklustre and narrow results. They have been superseded in the end by free-form language models (chatbots) that have no such inductive or structural biases. These latter have learned to apply logic only as needed within the context of generating text. Logic, in the end, has returned to its proper owner: language.

¹ In other posts I have described the causal utility that drives the formation of new thought associations. The use of logical operations fits neatly into that template, and is a particular application of it.

² Even this addition of logical elaboration is just another set of frames playing in the movie of the mind. It is not establishing any deeper structure beyond what is simply there in the content of the though-image. The presence of any “structure” in thinking is an illusion the mind convinces itself of.